Glam Metal and Its Requisite Gender-Bending: Celebrated Until They Suddenly Weren’t

Wearing my past like a merit badge, I’ve always been proud to have spent my teens and the bulk of my twenties in the 1980s — perhaps the most musically diverse and accommodating decade in popular music history. Likewise, I’ve never hesitated to openly profess my love for everything glam metal — the bands, the music, the big hair, the wild wardrobes, the excesses . . . everything. But not until I saw Sam Dunn’s A Headbanger’s Journey did I give much thought to the gender-bending that took place throughout the eighties — a phenomenon I was very much a part of without realizing it then or for some time afterward. While the world scoffed at Culture Club’s Boy George and his blatant androgyny and ambiguity, the masses seemed to be wearing blinders as glam metal’s Mötley Crüe, Poison, and numerous other L.A./Hollywood bands bent the male gender to unheard of and unimagined extremes. Glam and its requisite gender-bending were celebrated until they suddenly weren’t, and then the backlash was harsh and immediate.

Though the Finnish group Hanoi Rocks is sometimes cited as the first glam metal band, the moniker “glam” was first used in the early seventies. Glitter or glam rock — a smoother, more polished form of hard rock — emerged in the early seventies as a “backlash against the late sixties sexual revolution . . . revolving around a glorified sexual ambiguity and androgyny” (“Glitter” 218). Artists such as David Bowie and Marc Bolan (of T. Rex), along with bands such as Sweet, Slade, and Wizzard, wore ultra-stylish clothing, lots of makeup, and plenty of glitter (which gave the genre its name). Primarily a British happening, glitter rock was represented in America by the New York Dolls (glitter punks) and later, to some extent, by bands like Kiss. In England in the late seventies and early eighties, the glitter bands were revered by new metal groups such as Def Leppard, which borrowed from them musically while eschewing their glitter couture. [1] The up-and-coming Hollywood glam metal bands, however, while influenced by glitter to some degree, took their primary inspiration from Hanoi Rocks. Hanoi singer Michael Monroe cultivated an “ultra feminine urchin image” and, with makeup and jewelry, “pushed the limits of androgyny to extremes at a time before it was safe” (Christie 156, 157). Hollywood’s Mötley Crüe initially affected a tough look, mixing long hair and leather, then later appropriated Hanoi’s gypsy image, wearing makeup, female undergarments, and stacked heels.

In late 1983 and early 1984, MTV couldn’t get its fill of Mötley Crüe, saturating the airwaves with “Looks That Kill” and, in 1985, “Smokin’ in the Boys’ Room” and “Home Sweet Home.” Mötley’s initial wave of success unlocked the doors for other glam bands — Helix, Quiet Riot, Fastway, and Zebra, Dokken, Ratt, Twisted Sister, and Bon Jovi — but its mainstream breakthrough in and after 1985 literally threw open the glam metal floodgates. Honeymoon Suite, Krokus, Kix, Loudness, Black ’n Blue, Mama’s Boys, Cinderella, and countless others all had videos in rotation on MTV, were heard on the radio, and enjoyed all-important hit records. From this time onward, until the early 1990s, glam ruled the rock and metal worlds.

One of the bands that sprang from this mid-eighties heavy-metal fountainhead was Poison. In Los Angeles by way of Pennsylvania, Poison followed the Mötley Crüe model then did it one better. Glammed to the Max (Factor) and gender-bending to the point of actually looking like women, Poison, like the Mötleys, borrowed its fashion-sense from Hanoi Rocks while stealing its sound and musical direction from underrated seventies hard-rockers Starz. [3] (Poison’s “Fallen Angel” is a not-so-subtle rewrite of Starz’ “[She’s Just a] Fallen Angel,” while Starz’ “Cool One” could easily be mistaken for a Poison recording.) [4] In late 1986, just as it did with Mötley Crüe, MTV latched onto Poison and its “Talk Dirty to Me” video and by early 1987 had made the group the most visible and popular band in all of metal. Suddenly glam bands were everywhere. Suddenly, without anyone noticing, rock stars looked more than a little like women. Suddenly, with scarcely a word of protest, male fans of glam metal were emulating their musical heroes by growing their hair long and wearing that hair in unmistakably feminine ways. Ian Christie, in his Sound of the Beast: The Complete Headbanging History of Heavy Metal, writes that “glam metal in the 1980s was a testing ground for changing gender roles,” but it is more accurate to say that in the eighties glam metal tested just how far gender could be bent in order to be different, attract attention, and create sensation (156).

Nonetheless, no one expressed strong opinions about young men — glam rockers or glam fans — bending the male gender. No one seemed to express alarm like they did when Boy George and George Michael (of Wham!) were creating controversy with their gender-bending. In fact, the “glam look” became just one of the many personas males could adopt in the diverse, eclectic, and accommodating eighties. Perhaps this lack of concern was due to the overt masculinity still exuded by glam rockers: most were or wanted to be seen as wild children and bad boys — fighters, partiers, and womanizers. The Crüe’s “Bad Boy Boogie” stated it plainly: “Better lock up your daughters when the Mötleys hit the road.” Many glam rockers had sexy, even famous, girlfriends — Heather Locklear, Pamela Anderson, Tawny Kitaen, Cher, and Ally Sheedy among them. And their songs often contained macho, tough-guy lyrics: “The word is out, there’s gonna be a gang fight / Everybody knows that something’s going down.” [6] But if anything gave glam rockers continuing cachet it was that females were head-over-heels crazy about them. Until the eighties, few women attended heavy metal rock shows. But the emergence of glam metal changed all that, attracting and creating a manic female fan-base that purchased albums, went to concerts, and loved hard, metallic music. The members of Celtic Frost were thrilled to see females at their shows when they arrived in America, while Geddy Lee thanked the glambangers in Mr. Big, the opening act on Rush’s late-eighties tour, for drawing women to concerts — a new experience for Lee and bandmates Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart (Christie 170; Konow 269–70).

While androgyny in popular music can be traced to Frank Sinatra (whose slight physique and delicate vocal delivery was, in the forties, considered “transgressive”), androgyny and gender-bending truly entered the world of rock in the early sixties with the Beatles (Hajdu 67). Writer Steven Stark suggests that the Beatles’ matriarchal upbringing (the influence of women in charge of families while men were at sea and war), the influence of American girl-group songs (from which Liverpool songwriters learned to speak from female points of view), and the loss of their mothers (in the cases of McCartney and Lennon) made them markedly different from the typical males in females’ lives. Attracted to these “feminine” differences — hair, clothes, voices, lyrics, social attitudes — young girls identified strongly with the boys in the band, seeing themselves in the four Beatles. Since this time, contends Stark, women have been enamored with male performers who look like they do, with men who look like women (“First Rumblings”).

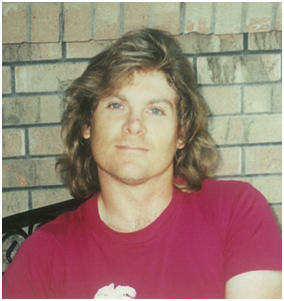

Stark’s supposition proved especially accurate during the late eighties, when females were drawn to glam rockers like moths to flames; Poison’s concerts were particularly notable for all the “Pick Me, Bret!” signs that women in the audience waved at the band’s singer throughout its shows. On the street and closer to home, I was never more popular with girls than after growing my wavy blond hair long in 1986 and keeping it at shoulder length until 1994. After wearing my hair short for nearly 15 years, and after missing the female attention I once took for granted, I grew my eighties hair back in 2009 and confirmed Stark’s thesis: a succession of girls in their mid-twenties expressed serious interest in me — despite the fact that I was 47 years old. Giving further credence to Stark’s supposition I, while at the Lafayette Flea Market around this same time, spotted a girl of no more than 14 or 15 clutching a 20-year-old Poison poster like it was the find of the century. There was definitely something at work in the way women were drawn to glam rockers, something a bit unusual, just as there was something a bit odd in the way straight/heterosexual men were drawn to heavy and glam metal and the mostly male performers who made the music.

In A Headbanger’s Journey, Dunn touches upon the strange, contradictory nature of the relationship music fans had with metal during the eighties. In one corner of this metal world, straight men and women were hard-core followers of heavy metal groups like Judas Priest, whose singer Rob Halford was gay — though no one knew it at the time. Halford wore studded black leather and wielded whips and chains, all paraphernalia borrowed from gay/sadomasochistic culture — which straight fans knew nothing about either. Metal heads simply enjoyed the shows and rocked out to the music, oblivious to all the gay and S&M references. In another corner of this world, straight men and women were serious fans of glam bands like Mötley Crüe and Poison, whose members sported feminine attire and often looked like women — without being gay. These fans also enjoyed the shows and rocked to the music while oblivious to all the gender-bending.

The incongruous relationship Dunn examines is indeed peculiar. But in addition to idolizing gay performers pretending to be macho in black leather and making heroes of straight men feigning toughness while dressed like women, straight males and females engaged in two other behaviors not mentioned or explored by Dunn that made fans’ attachment to the music stranger still: Glam’s more dedicated adherents — straight men dressed like women in emulation of their glam heroes — watched and rocked to other straight men dressed like women while all involved were completely secure in their heterosexuality. Add to this the straight women who were sexually infatuated with glam rockers — men who dressed and looked like their female fans — and we have perhaps the oddest chapter in rock ’n roll’s wild, crazy, and sordid history. Eighties glambanger Dee Snider of Twisted Sister, when talking with Dunn about this odd moment in time, says:

“An intriguing thing about heavy metal music during that period is how [there was] the feminine preening on one side and the ultra-masculine cock rock strutting in skin-tight, ‘check-out-my-bulge’ pants [on the other] for an audience that was 90% male. Any way you slice it there was something really homoerotic about it and bizarre. There’s definitely some weirdness about males viewing guys looking like women [and] males viewing men being very strutty [with that] West Village, gay, leather look. Really, some doctors need to look into this!” (qtd. in Headbanger’s Journey 00:50:34–51:14)

“I don’t know how to explain it,” adds Snider, “but I never questioned my sexuality at any point, and I was up there [on stage] in lingerie. My wife . . . was the one dressing me up half the time” (00:49:19–30).

Despite all the weirdness, which few recognized or fully comprehended at the time, glam metal remained hugely popular. But not all was well within the genre. Glam metal and its gender-bending were not celebrated or tolerated by everyone. Hanoi Rocks’ Monroe tells of an early-eighties visit to the band’s record company: “We went to do press at our label, and when I went to the men’s room, all the men had to leave because they were too intimidated [by my jewelry and makeup]. That was weird. I was going, ‘What the hell is this?’” (Christie 157). And the guys in Skid Row tell of going out in public in the late eighties with “their hair stacked to the sky” and fighting with rednecks who called them faggots (Konow 296). While I never had to duke it out with anyone because of my long hair (the extent of my glam look), I did have similar experiences in the real world. Once, when with my mom at Huntington House, a now-defunct furniture store, a female sales clerk came up behind us and asked, “Can I help you ladies?” And on another occasion, when looking at clothes at Joslins in the Westminster Mall, a woman approached me from behind while remarking, “What do we have here? A lady looking at men’s pants!” The most remarkable incident, however, occurred in 1991 when I was a student at Front Range Community College in Westminster: While standing at the urinal in the bathroom, a man walked in, spotted me, then conspicuously took a half-step back out of the doorway in order to lean over and reread the “Men” sign on the wall. It was his overt way of expressing disapproval with my look. In the moment, I thought his behavior was strange and uncalled for when, instead, I should have recognized that all my run-ins with polite society, and all of glam’s with the straight world, were the tell-tale signs of glam metal’s imminent demise, the wind of change blowing through popular music once again. “I kind of thought everything would remain the same forever,” says producer Tom Werman. “I thought [there would] always be hard rock . . . . I had no idea that the nature of the music would change. I never factored change into my life or anyone else’s” (qtd. in Konow 385).

But the music did change. And when the Hollywood glambangers’ glow began to fade, when heavy metal started to lose its popularity and experience the first waves of rejection in the early nineties, all the followers in that parallel reality called glam fandom were rejected as well. At the same time that Warrant singer Jani Lane found himself in the Columbia Records office in 1992 staring at a giant poster of Alice in Chains where a poster of his band used to hang, at the same time that Mötley Crüe’s Nikki Sixx found himself playing for 50 kids in 1994 and realizing that “it was all over,” glam metal’s devoted adherents also found themselves on the outside looking in (Konow 352; Strauss 282). I went from having females grant me rock star-like attention in 1991 — from having a girl stop dead in her tracks and exclaim “Oh, my God!” when she saw me walking down the hallway at Front Range Community College (like I was Jon Bon Jovi or somebody) — to being mistaken for a woman at the Gemini restaurant in Wheat Ridge in 1993 and later suspected of shoplifting at KG Mens Store in the Westminster Mall. Heavy and glam metal were under attack, and like the glam rockers who were now being shunned and shoved aside, I too was suddenly treated differently — with scorn, suspicion, and condescension. Suddenly “it was all over” for me too (and for my glam metal brethren). I was now an anachronism when only moments ago I had been the coolest of the cool.

My sudden loss of “fame” and popularity, the sudden end of my “15 minutes” in the spotlight, was hard to accept. But whereas I could simply cut my hair and more or less carry on with life, carving out a new identity while the larger part of my world remained unchanged, heavy and glam metal artists had to struggle and come to grips with the abrupt loss of real fame, fantastic popularity, and flourishing careers. [7] Believing that the music and the times would never change or end — another fanciful notion held by rockers and fans throughout the eighties — left many unprepared for the future when inevitable change finally did arrive. When trying to explain the rise of glam metal and its androgyny and gender-bending, musicologist Robert Walser of UCLA says, “It shows that so many of the things we take to be natural and unchanging and ‘just the way they are’ are not just the way they are” (qtd. in Headbanger’s Journey 00:50:27–33). While this is indeed true, is it also true that unforeseen change often abruptly changes back again, thus taking everyone by surprise once more when things return to natural and normal. Case in point: When rock music returned to a safer, less-audacious mindset in 1993, swinging back once again, glam’s instant irrelevance took many by surprise — especially glam rockers and glam fans.

Glam and its requisite gender-bending were celebrated until they suddenly weren’t, and then the backlash was harsh and immediate, bringing a swift end to the exhilarating, intoxicating eighties — a decade that was more colorful, more outrageous, more diverse, more accommodating, and perhaps more difficult to let go of than any other before or since.

Above piece excerpted from the forthcoming It’s Only Music: A Musical and Historical Memoir.

[1] Interestingly, Leppard guitarist Phil Collen, who was recruited from the “rouge ’n roll” group Girl, once played with a glitter band called Dumb Blondes, whose members wore female clothing and mascara and were heavily influenced by the New York Dolls. “We did the whole bit,” says Collen. “Stacked heels, black lipstick. We’re talking major embarrassment here” (qtd. in David Fricke’s Animal Instinct: The Def Leppard Story. Zomba Books, 1987. 78–79).

[3] “As one Guitar World writer put it, ‘Anyone who dares to claim that his first reaction to the cover of Poison’s debut wasn’t “Whoa! These chicks are hot!” is a lying sack of s##t’” (Konow 265).

[4] “Fallen Angel” by Poison; #12, 1988. “(She’s Just a) Fallen Angel” by Starz; #95, 1977. “Cool One” by Starz; 1977.

[6] “Blood on the Bricks” by Aldo Nova; 1991.

[7] One such example is David Lee Roth. Separated from Van Halen and a once-relevant solo career, Roth gigged in Las Vegas for a short time in 1995 then worked as a paramedic in New York City as the nineties moved into the first decade of the new century. Roth got lucky, however, when he was invited to rejoin Van Halen in 2007 and has since spent most of his time playing sold-out shows in Japan, continuing to enjoy some semblance of the adoration and star treatment he once knew. But few metal artists had Roth’s musical legacy to fall back on. Fewer still had his wealth and resources with which to search for thrills analogous to those of rock superstardom when their time in the limelight was over. As a result, many had trouble returning and adjusting to normal life. I was only a zealous fan and ardent lover of the music, but even I had trouble letting go of the eighties. When I regrew my long hair in 2009, it wasn’t to confirm Stark’s ideas about gender-bending; it was, instead, an attempt to revisit and remake the past. And though women were attracted to me as strongly as ever, men despised and hated me. My male instructors and classmates at the University of Colorado at Denver and males in stores and on the streets all saw me as a weirdo; some were afraid to look me in the eye while others wanted to kick my ass. Long curly-girly eighties hair was out of place and simply unacceptable in the first decade of the twenty-first century. It was only then (20-plus years later) that I fully accepted the fact that the nineteen-eighties were over — dead, finished, kaput. (And that the diversity, tolerance, acceptance, and accommodation that were part and parcel of the decade had died as well.) Skid Row drummer Rob Affuso, who waged his own battle with the passing of the eighties and the loss of fame, says: “I can now see why so many ex-rock stars are drug addicts. You go through this incredible high, you’ve [attained] your dream, you’re living it, and then suddenly it’s over. You’re still trying to find that high and [many former rockers] look for it in drugs” (Konow 370).